Consent is a conversation; it is about communicating your boundaries.

Think about ordering a pizza with a large group of friends- there has to be a discussion about the pizza toppings. For instance, if one person is allergic to mushrooms- we know mushrooms are not an option for our order. A conversation is required to figure out what pizza toppings everyone is comfortable with ordering. Finding mutual consent is possible, no one wants the negotiation about the pizza toppings to turn coercive or mean if there are disagreements. This same principle applies when consenting to sexual activity.

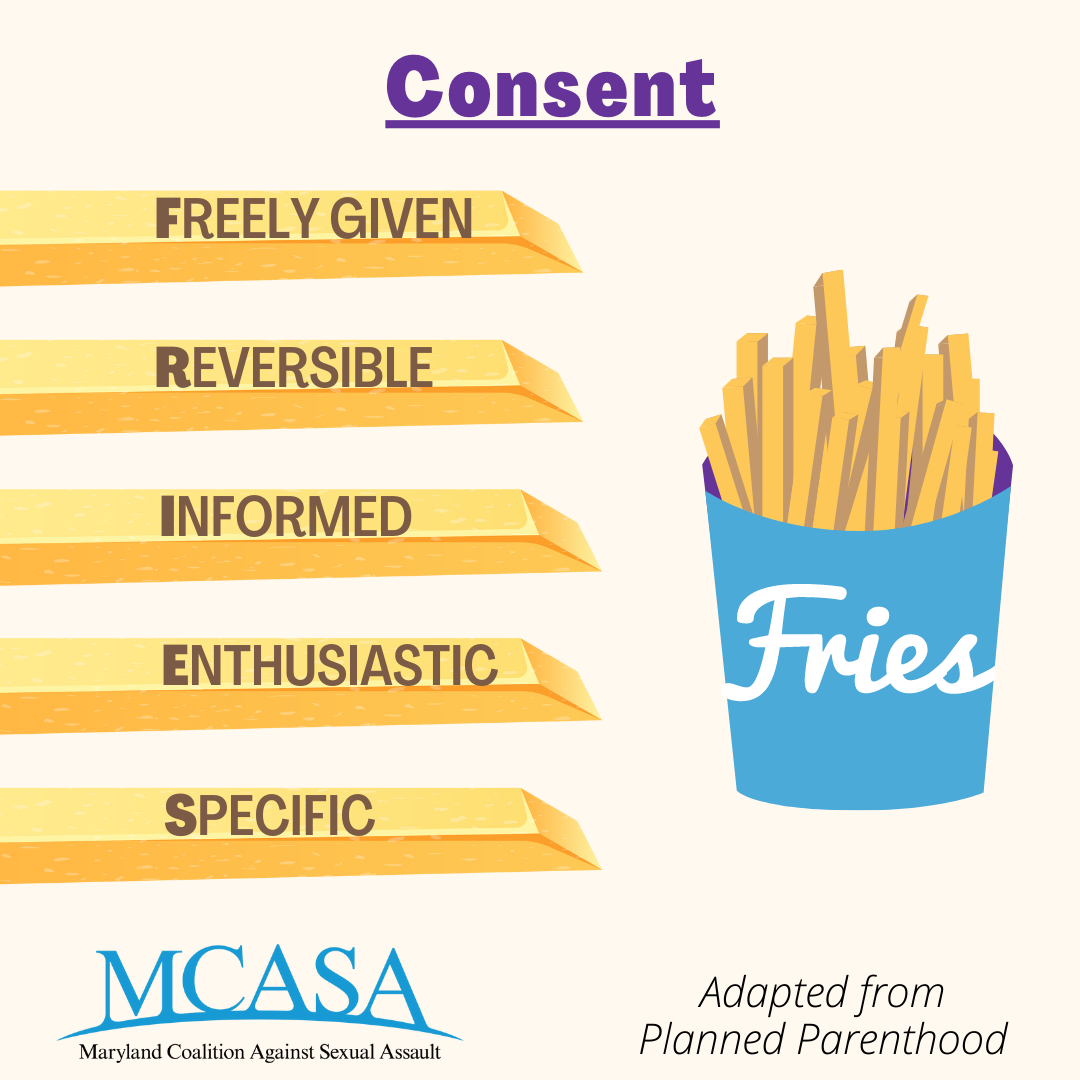

The following is adapted from Planned Parenthood.

We can use the acronym FRIES to outline consent:

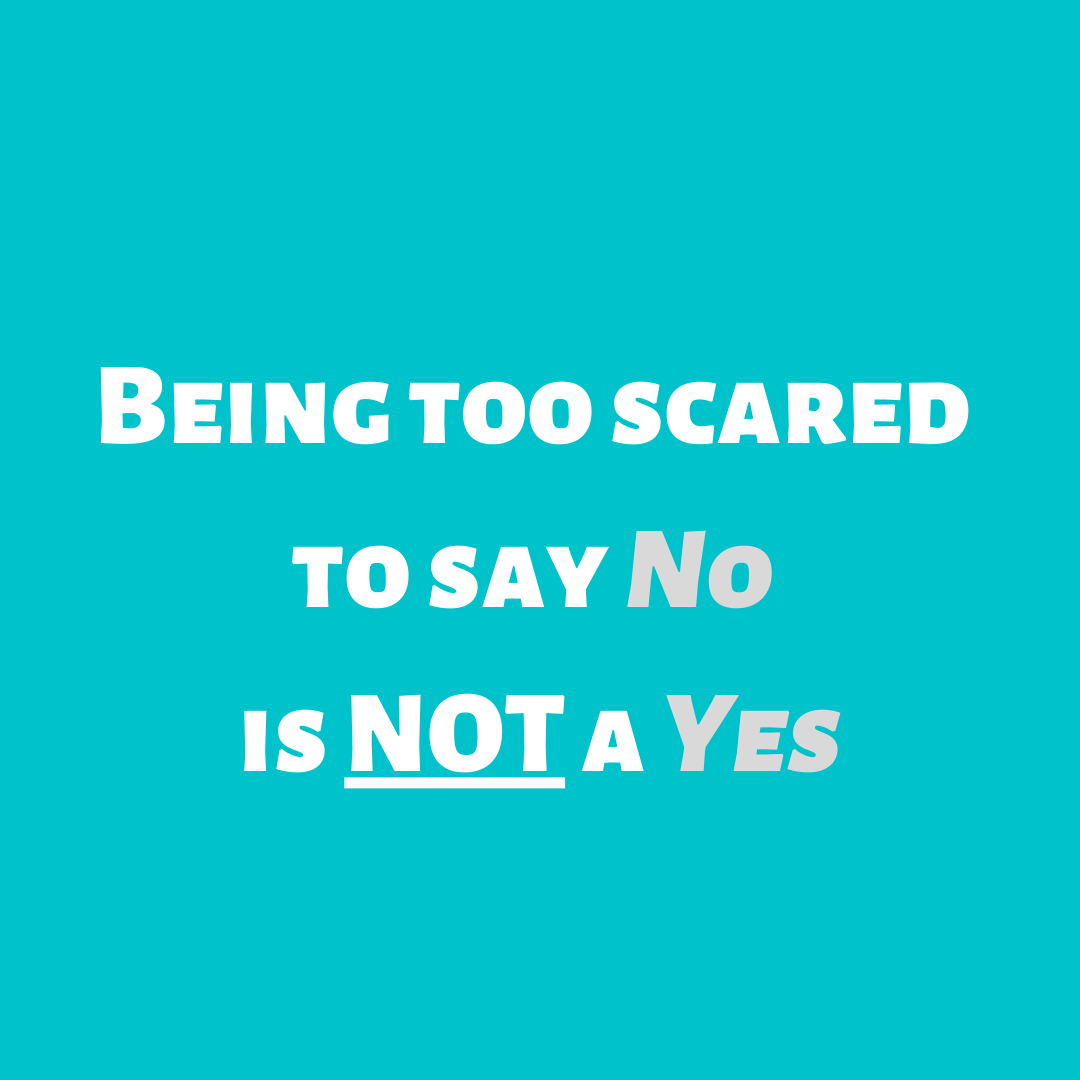

Freely given. Consenting is a choice you make without pressure, manipulation, or under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

Reversible. Anyone can change their mind about what they feel like doing, anytime. Even if you’ve done it before, and even if you’re both naked in bed.

Informed. You can only consent to something if you have the full story. For example, if someone says they’ll use a condom and then they don’t, there isn’t full consent. If it’s not clear, it is not consent.

Enthusiastic. When it comes to sex, you should only do stuff you WANT to do, not things that you feel you’re expected to do.

Specific. Saying yes to one thing (like going to the bedroom to make out) doesn’t mean you’ve said yes to others (like having sex).

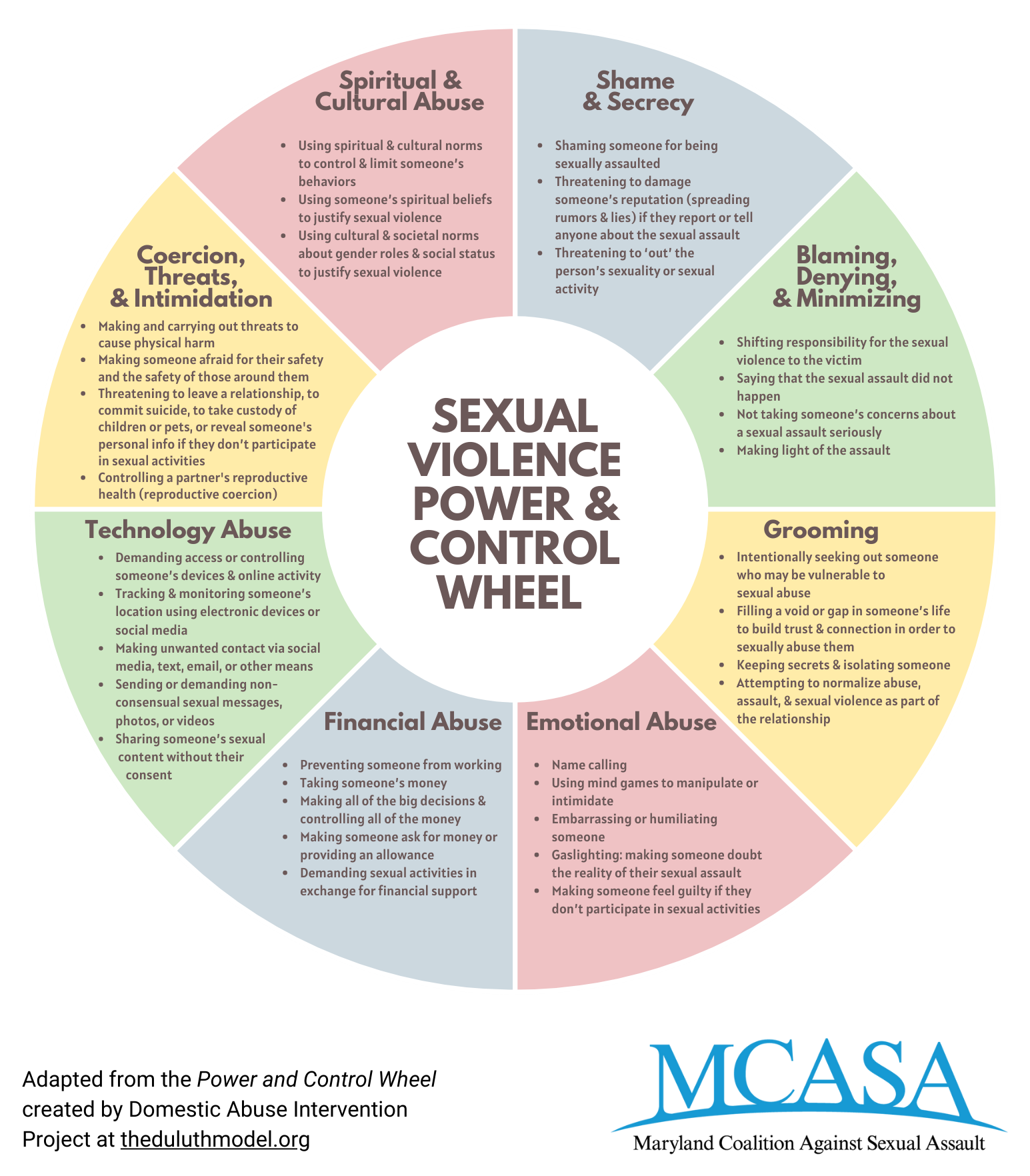

Sexual violence is a form of power-based violence. One party seeks to control another by exerting power over them. Sexual violence is used to gain power over someone else. People who cause harm may use sexual violence to manipulate their victims.

We know sexual violence does not discriminate by age, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious identity, race, or enthicity. However, we also know that women, LGBTQIA+ people, communities of color, and people with disabilities are more vulnerable to experiencing sexual violence. This is directly due to historical and existing societal structures that oppress marginalized populations. Systemic power dynamics are replicated in interpersonal relationships in which perpetrators use violence to assert power and control over their dating and intimate partners. More than 1 in 4 women and more than 1 in 10 men have experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner (CDC, 2014).

Check out the Power and Control Wheel below to see examples of relationship and intimate partner power dynamics that are warning signs of unhealthy and abusive situations. These tactics can also be used by perpetrators of sexual assault to coerce victims and instill fear of retaliation or further harm if they come forward about the assault.

![]() Rape culture is the way that our society minimizes the severity of sexual violence and normalizes attitudes and beliefs that defend perpetration of sexual violence. Victim blaming is a symptom of rape culture that occurs when the victim of the sexual violence is held at total or partial fault for the harm that they experienced. The “just world hypothesis”, which is the idea that people deserve what happens to them, is often credited as one mindset that may enable victim blaming in our culture.

Rape culture is the way that our society minimizes the severity of sexual violence and normalizes attitudes and beliefs that defend perpetration of sexual violence. Victim blaming is a symptom of rape culture that occurs when the victim of the sexual violence is held at total or partial fault for the harm that they experienced. The “just world hypothesis”, which is the idea that people deserve what happens to them, is often credited as one mindset that may enable victim blaming in our culture.

Victim blaming can be subtle or direct. For example, asking a victim what they could have done differently to prevent a sexual assault is holding the survivor accountable for the harm doers actions.

Victims are never at fault- it doesn’t matter what someone was wearing, or if they were drunk, or how they were acting. No one ever asks to experience sexual violence. The only person who makes the choice to cause harm is the harm doer. Call out victim blaming in every form!

Check out the following video ‘What is Rape Culture?’ from the Nova Scotia Government to learn more about rape culture. Check out this video from Bangor University to learn more about victim blaming language and behavior.

Digital consent is about asking, seeking, and receiving permission online. It is a way of referring to consent that happens through screens. Just like in-person sexual activities, consent should be an ongoing discussion when communicating digitally. Whether messaging, video chatting, gaming, or connecting on other online platforms, we need to respect digital boundaries.

Digital consent is about asking, seeking, and receiving permission online. It is a way of referring to consent that happens through screens. Just like in-person sexual activities, consent should be an ongoing discussion when communicating digitally. Whether messaging, video chatting, gaming, or connecting on other online platforms, we need to respect digital boundaries.

Digital boundaries dictate what someone is comfortable with. A digital boundary could be restrictions around sharing internet passwords, asking permission before sending intimate texts or images, or rules about what content someone is comfortable sharing online with another person.

Consider how your actions online might make others feel. Respect boundaries with your partner when it comes to sexting or sharing information online.

Consent is about communicating and respecting boundaries. Before we cross boundaries, we must ask for consent! When someone crosses another person’s boundary without their consent, that is NOT okay.

Consent is about communicating and respecting boundaries. Before we cross boundaries, we must ask for consent! When someone crosses another person’s boundary without their consent, that is NOT okay.

One way that adult caregivers can protect children is to talk to them about personal boundaries and obtaining consent. Personal boundaries are rules and limits a person creates for themselves. Boundaries can establish what (if any) kind of physical contact with other people is appropriate. Demonstrating boundaries with children from a very young age, even as toddlers, shows children that every individual can assert bodily autonomy. One way to support children in setting boundaries includes allowing children to choose if they want to hug a family member or friend. It’s important for children to understand that they do not have to touch anyone they don’t want to, even if it is a kiss and a hug.

We can educate children from an early age about setting boundaries and respecting consent. By doing so, we provide kids with a sense of autonomy over their own bodies. Not only does instilling a sense of autonomy in child protect the child from sexual abuse and grooming, it can also help your child have healthier relationships in the future.

For younger kids, the conversation about consent can start long before the conversation about sex. Consent simply involves respecting other people’s boundaries. It is permission for something to happen or an agreement to do something. Emphasize to your child that when asking someone to consent to something (like a hug), it should be assumed the default answer is “no” because consent must always be obtained through a verbal “yes.” Consent can be demonstrated to kids when play-tickling. If the child asks to stop being tickled, or says “No,” listen and show your child that no really means no.